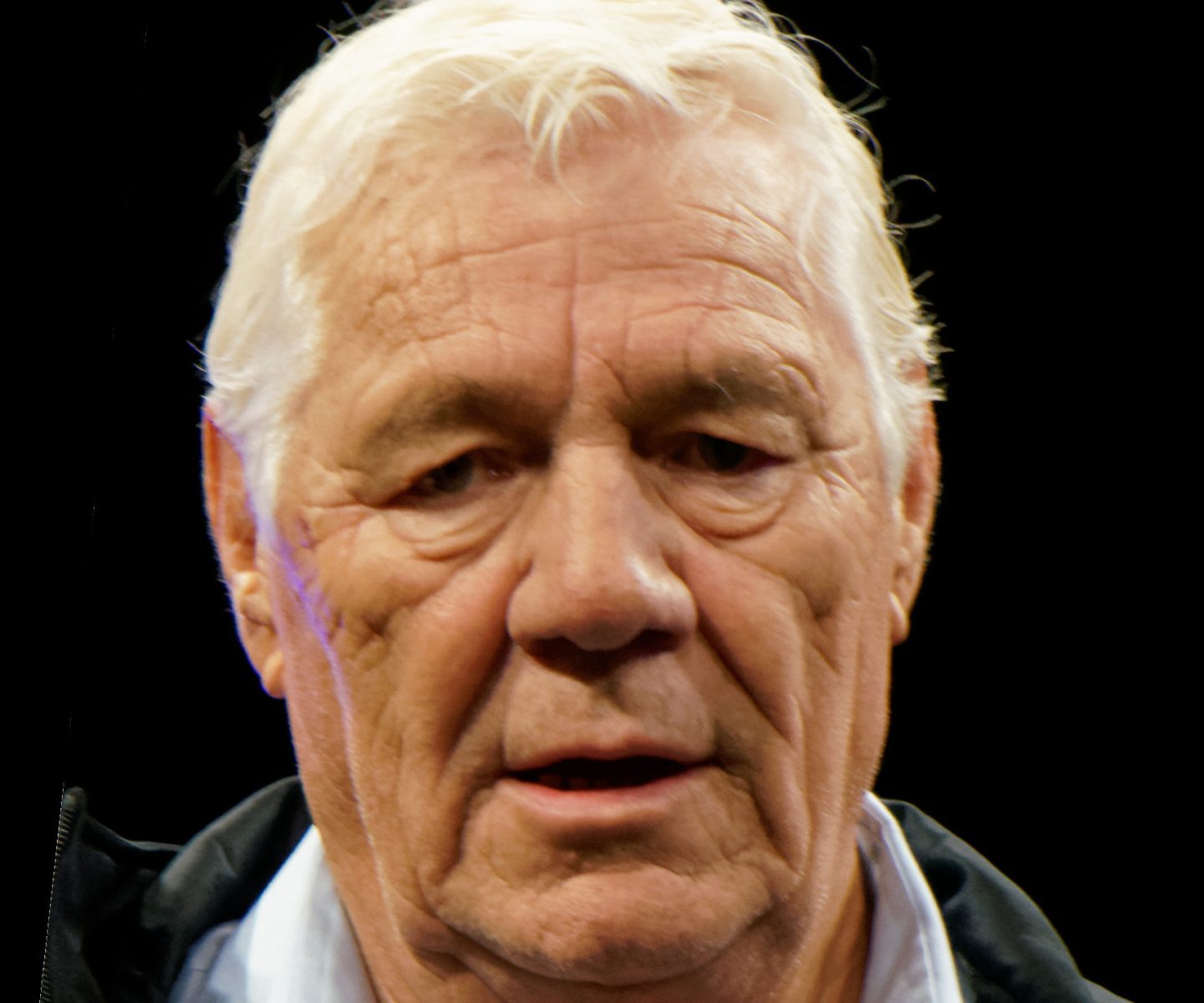

Buddy Rogers, 1921–1992

He sold elegance like a weapon. In an industry built on sweat and blunt force, Buddy Rogers walked in looking like he’d never had to raise his voice in his life. That was the trick. The “Nature Boy” didn’t need volume. He had posture, timing, and a kind of polished cruelty that made crowds feel like they were being insulted personally—and paying for the privilege.

Ring Names: (In order)

- Buddy Rogers

- Nature Boy Buddy Rogers

Rogers is one of those names that still hangs over pro wrestling like cigarette smoke in an old arena. You don’t have to like him to understand the shape of what he helped create: the idea that a champion could be a star first, a fighter second, and a villain always—because villains, when they’re good enough, sell the most tickets.

The Look That Changed the Room

Rogers didn’t present himself like a working-class brawler. He presented himself like a man who believed the world owed him something. That mattered in mid-century wrestling, where the champion wasn’t only a belt-holder. He was a traveling billboard for the entire business.

He leaned into vanity and made it feel dangerous. The bleach-blond hair. The strut. The sense that he was performing superiority, not simply claiming it. Fans didn’t just want to see him lose. They wanted to see him humbled. That’s a different kind of heat—more intimate, more emotional, and harder to manufacture.

And Rogers manufactured it anyway.

A Prototype for the Modern “Star” Heel

If you trace the lineage of wrestling’s most influential archetypes, Rogers sits near the root of one of the biggest ones: the charismatic, image-conscious heel who treats the ring like a stage and the audience like a jury.

He wasn’t the first villain. He wasn’t the first pretty boy. But he helped fuse those ideas into a single, marketable identity—one that could headline, travel, and draw money across territories. The “Nature Boy” label itself became a template other wrestlers would later borrow, rework, and build careers around.

That’s the kind of influence you can measure without needing to exaggerate it.

The Champion as a Business Plan

Rogers’ era was an era of gate receipts and local promotion, where the champion’s job was to make the next town care. A champion who looked like a star and acted like a scoundrel could do that reliably. Rogers fit the role with unnerving precision.

He understood something that still holds true: fans will forgive almost anything if you make them feel something strong. Rogers made them feel disrespected. He made them feel played. He made them feel like the world was unfair—and then he offered them a ticket to watch fairness try to fight back.

Legacy: The Strut That Echoes

Rogers’ legacy lives in the performance of arrogance as craft. In the way heels learned to weaponize presentation. In the idea that a wrestler’s identity could be as carefully designed as a movie character’s wardrobe.

Buddy Rogers didn’t become the first WWWF champion by surviving a tournament or grinding through a new company’s ranks; he became champion because the new promotion said he was. When the World Wide Wrestling Federation split off in 1963, it recognized Rogers as its inaugural titleholder after he “won” a one-night tournament in Rio de Janeiro, a piece of instant mythology that did the job of making a belt feel older than it was.

The reign itself was even shorter than the story that launched it: Rogers dropped the championship to Bruno Sammartino on May 17, 1963, at Madison Square Garden, losing in 48 seconds after Sammartino worked his neck and Rogers couldn’t continue—an abrupt ending that, in its own way, told you what the new company wanted next: a durable, homegrown champion, not a traveling “Nature Boy” propped up by a faraway tournament.

Rogers also lives in the uncomfortable truth that wrestling, at its most effective, often runs on the energy of people wanting to see a beautiful liar finally get what’s coming.

Rogers made that liar believable.

Leave a Comment