André the Giant, 1946–1993

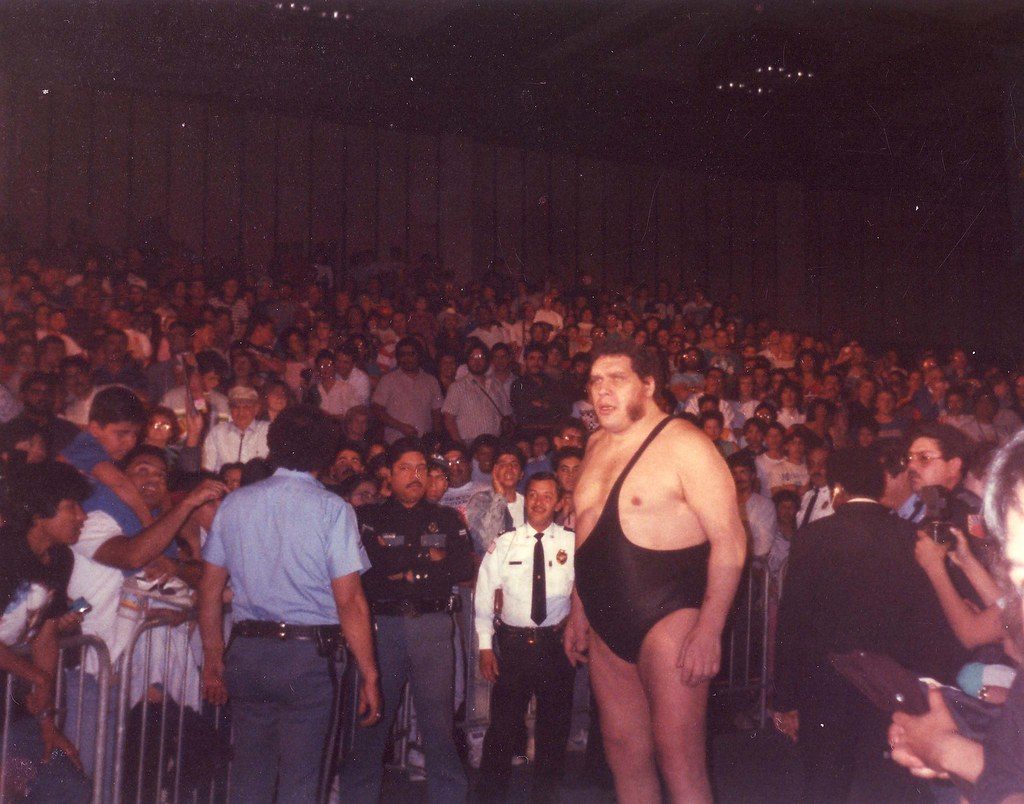

There are wrestlers who get over because they’re great talkers. Others because they can fly. André the Giant got over because he walked into a room and the room changed shape around him.

Ring Names: André the Giant; André Roussimoff; Jean Ferré; Giant Machine

For decades, promoters sold him as “The Eighth Wonder of the World,” a line that sounds like carnival copy until you remember what wrestling was built on: the promise that you might see something you’ve never seen before, and might never see again. André made that promise feel credible. His size did the talking first. The mystique followed.

André René Roussimoff was born in Coulommiers, France, and his extraordinary height and strength came from acromegaly, a condition that causes abnormal growth. In wrestling, that kind of reality doesn’t get hidden. It gets framed, lit, and turned into a main event.

Promoters understood quickly what they had: a special-event attraction who could be dropped into any territory and instantly elevate a card. That’s the key to André’s early career, and it’s easy to miss if you only know the later, more televised version of him. By the time American audiences widely embraced him, André wasn’t a novelty being introduced. He was a proven international draw.

He worked extensively across Europe, Japan, and North America, and Japan in particular fit him. The country’s larger-than-life presentation of heavyweight wrestling matched his size and power, and he became a must-see name for promoters trying to pack arenas. The formula was simple and effective: put André on the poster, and people showed up to confirm the rumor with their own eyes.

In the United States, his legend grew through years of protected booking that emphasized aura and near-mythic invincibility. Wrestling has always understood scarcity. André wasn’t treated like a weekly television fixture. He was treated like weather: something that arrives, changes everything, and leaves people talking about what they just lived through.

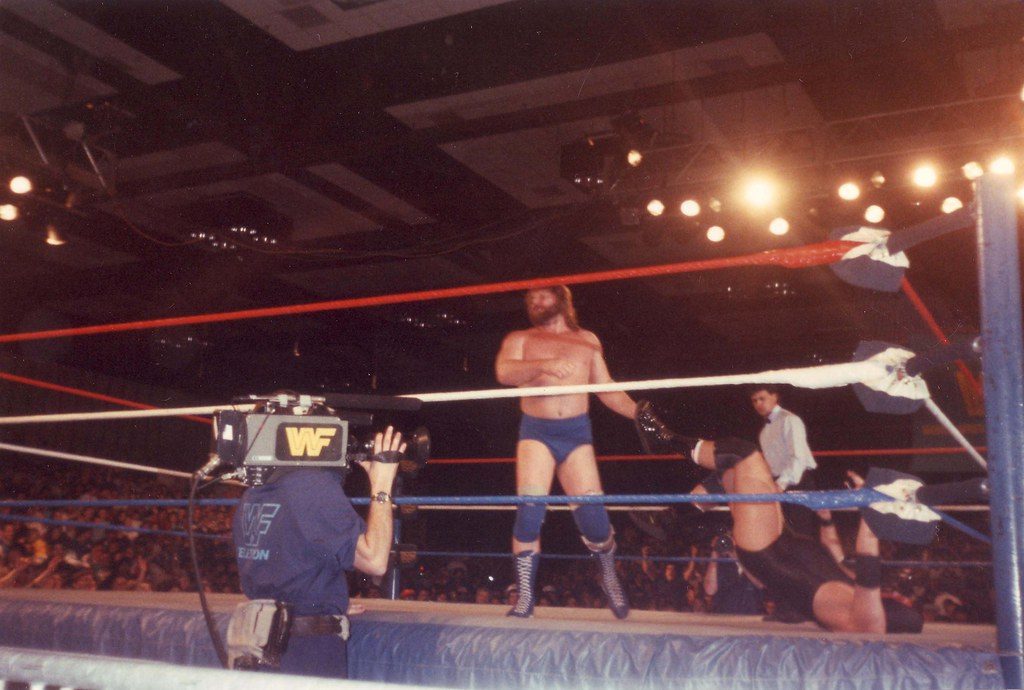

That approach reached its peak during WWE’s national expansion in the 1980s, when André became a centerpiece of the company’s biggest moments and storylines. The most famous chapter came opposite Hulk Hogan, with André positioned as the unbeatable giant and Hogan as the heroic champion. Their rivalry culminated in a defining WrestleMania moment, one of the era’s signature attractions and a cornerstone of WWE’s historical narrative. It worked because it was clean storytelling: the immovable object, the unstoppable force, and a crowd asked to pick a side.

Outside the ring, André did something few wrestlers of his time managed: he crossed into mainstream entertainment without shrinking himself to fit it. His role as Fezzik in The Princess Bride introduced him to audiences who may not have followed wrestling, and it cemented his status as a rare athlete who could become a true pop-culture figure. He didn’t have to explain wrestling to those viewers. He just had to be André.

The later years were harder. The physical toll of acromegaly and the grind of wrestling’s travel schedule shaped the back end of his career. Even as his mobility declined, his name value stayed enormous, and promoters continued to use him as a special attraction. That’s the business, at its most honest and its most unforgiving: the thing that made him a phenomenon also made the work heavier, year after year.

André died in 1993 at 46. The legacy didn’t need much help after that. It lived on through wrestling’s biggest stages, through the stories told by generations of wrestlers who shared locker rooms with him, and through the lasting image of a performer who made “larger than life” feel literal.

Leave a Comment